History

We recognize that to transcend where we are, we must include the history that brought us here. Trinity House Catholic Worker is an inclusive contemplative community rooted in the tradition of The Catholic Worker movement of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin.

GUIDANCE

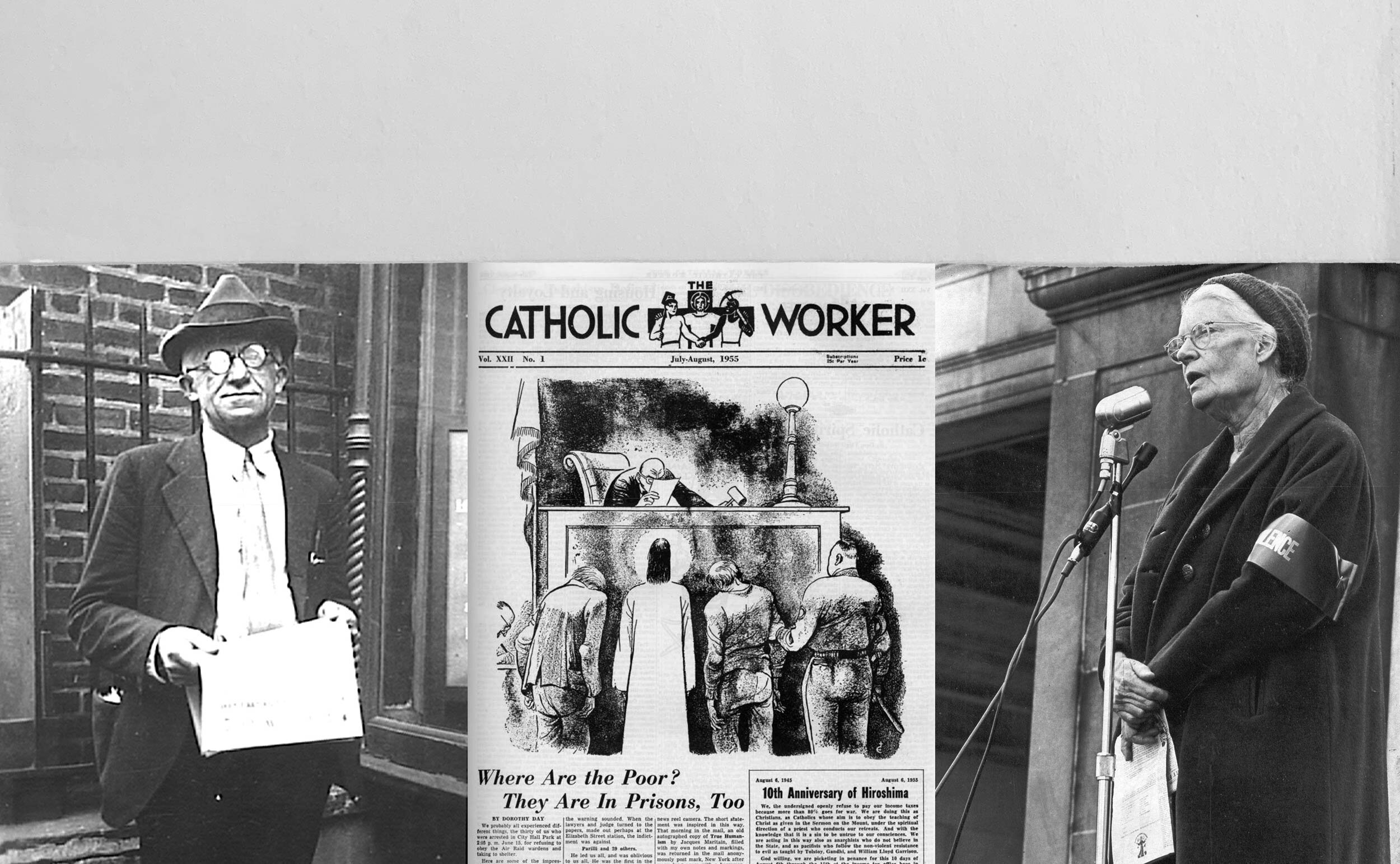

Peter Maurin left his birth country, France, traveled to Canada, and eventually came to America in 1911. He wandered from job to job and city to city, penniless. In 1925 he accepted an invitation to move to New York City and there he began to speak out about his convictions, meeting with people to discuss how to implement his ideas. He met with Dorothy Day in December of 1932 and by May of 1933 the first issue of the Catholic Worker was published. He saw parts of his plan come to fruition during the next several years, including Round Table Discussions, Houses of Hospitality, and Farming Communes. He died on May 15, 1949 at the farming commune of Newburgh.

PHILOSOPHY

A life of poverty is a life that emulates the person of Jesus Christ. Suffering through giving up all material goods on this earth is to join in suffering with Christ because he gave up everything. After the model of Saint Francis, Maurin dedicated his life to poverty. Through becoming poor, one followed Christ and embodied the salvation message that Christ preached. For Maurin this poverty was also a witness to the community around him. It challenged them to forget the material and embrace the spiritual. If a community would adopt poverty, they too would emulate the message of Christ. Maurin believed this to be the road to the spirit and freedom. A person became free through giving up everything and becoming dependent upon God. By giving up all, life became focused on prayer and service. The community was now easily able to encourage cooperation and tend to the spirituality of the individual. This was the way to rebuild the Church and a new social order—through faith and contemplation, not through seeking affluence.

THE CATHOLIC WORKER

Peter Maurin wanted to transform society. The Catholic Worker movement was founded to spiritualize the social order. Along with Dorothy Day, he proposed a personal, decentralized society, a village-functional economy, and a life with spirituality as its center and an obligation to neighbor.

Round Table Discussions, Houses of Hospitality and Farming Communes – those were the three planks in Peter Maurin's platform. A strong believer in education through dialogue, Maurin advocated "round table discussions for the clarification of thought." Friday night meetings quickly became a tradition of the Catholic Worker community.

1| ROUND TABLE DISCUSSIONS

Peter Maurin wanted to see people from various philosophical viewpoints come together and discuss their thoughts. By engaging in conversation, intellectual positions could be clarified. Maurin wanted both scholars and workers alike to attend. He felt that society had placed a sharp division between these two groups and that at the round table a common understanding could be reached that would benefit both. It was at these discussions that Maurin would reveal his plan for society. He wished to discuss the ills of society, the ideal solution, and then discover the path that would lead the social order where it ought to go. Then both the scholar and the worker would be prepared to do his part in forming the new social order.

2| HOUSE OF HOSPITALITY

The next part of Maurin’s plan was to develop “Houses of Hospitality.” Drawing from the medieval practice of providing shelters for the wanderer, Maurin wanted to see houses where the more fortunate could help those who were in need. This met a variety of needs, not the least of which was to help alleviate the suffering of many from the Great Depression. But the House of Hospitality was also a place where the rich had the opportunity to fulfil Christ’s command to love and serve others. The houses were to remind society of the vision of sacrifice and service to those in need.

3| FARMING COMMUNITY

The final part of Maurin’s social program was to create farming communities, in an attempt to bring about a cultural agrarian economy. The machine was increasingly replacing workers in the factories of the cities, which meant that workers were being increasingly displaced. The solution was to return to the land and let it support them. A return to the land would stop the unemployment that Maurin felt was inherent within an industrial economy and would provide for a more just and stable society. Agronomic Universities of Farming, as Maurin called them, were places where the city dweller could go and receive training in farming and crafts. Here subsistence farming and crafts were practiced; these would direct the forces of production toward need as opposed to profit. Values of cooperation and the spiritual dimension of man would be recovered here as well. This movement was to be a personalist movement in which cooperation and goodwill were emphasized as an essential dimension of community life. Maurin believed in his idea of returning to the land so strongly that he later equated returning to the land with returning to Christ.

2004

In 2004, A series of pivotal meetings were held on Trinity Sunday (a Feast Day) and on New Mexico’s Nuclear Disaster Day (a Famine Day, a.k.a. Trinity Bomb Day and Church Rock Uranium Spill Day. These meetings led to monthly round-table discussions and the opening of Albuquerque's second Catholic Worker community, Trinity House Catholic Worker (THCW). Initial support came from the Unitarian Universalists, Catholic Sisters, Mennonites, and Nuclear Abolitionist allies from the ABQ Peace and Justice Center.

2005 – 2011

Led by Marcus Page, in 2005 THCW began serving free lunch to the poor and homeless of Albuquerque, NM. By mid 2005 residency was opened at the House for two homeless guests and one volunteer – more workers and guests came and the 8 bedroom layout began housing up to 4 workers and 4 guests at any given time for the next 6 years. Along with residential hospitality THCW provided other ministries such as free pop-up grocery stores, raising awareness of nuclear abolition & environmental issues, a roving public toilet, and the beloved “Breakfast, Laundry, Shower” (BLS). Beautification projects and rehabilitation for the building began. Transitional housing was a large component of the anti-homelessness work THCW did during this beginning phase. The tight relationships between Workers and guests was a hallmark of the Catholic Worker charism. Many folks transitioned, and numerous volunteers grew spiritually in part through voluntary contact with the homeless folks, who often became volunteers before transitioning out.

2012-2013

In 2012 came the advent of “The Manger” a shared responsibility between live-in and non-live-in volunteers from the THCW community. “The Manger” became the primary ministry of the House. By early 2013, Chelsea and Marcus left THCW – the free pop-up grocery stores continued, and “The Manger” comprised THCW’s public ministry for the poor, marginalized and homeless which focused two bedrooms for homeless guest-families for a duration up to three months.

2014-2016

Under the direction of Dennis Murphy, the mission evolved: “We seek to imitate Jesus Christ, by living a particular, intentional lifestyle to co-create with God a community that is built on faith, love, hope, prayer for peace and social and environmental justice. We live to express the love of God by understanding, coming alongside, and addressing the pain of those in need, primarily helping the poor, marginalized, homeless, and immigrant families in Albuquerque, New Mexico to find pathways of transformation through the challenges they face.” Improvement and renovation projects continued on the house and the surrounding grounds.

2017-2019

In 2017 the ministries offered by THCW included: serving meals at the door to neighbors and local homeless folks, the free pop-up grocery stores continued on Saturday and Sunday mornings, and the house became a meeting place for weekly gatherings under the guidance of Swami Omkara. Spiritual seekers and pilgrims frequented the House and the weekly discussion groups (Richard Rohr’s daily meditations, Twelve Steps for Everyone, and The Bhagavad Gita) and monthly interfaith liturgical liturgies became staples of THCW community ministry.